Shattering the PoW Myth! The Largest Privacy Coin by Market Cap Suffers a 51% Attack — But Is Bitcoin Really Safer?

GM,

Even people who’ve never bought cryptocurrency have probably heard of “mining.” Everyone says mining consumes huge amounts of electricity—some even steal power for it. But what exactly does mining do? The recent 51% attack on Monero offers the perfect case study.

Monero is the world’s largest and oldest privacy coin 1, with a market cap of nearly $6 billion. Like Bitcoin, it uses a mining mechanism known as Proof of Work (PoW) to secure its blockchain against hackers.

But last week, Monero suffered a 51% attack that was publicly announced in advance. Despite the community’s defense efforts, the attacker ultimately succeeded in rewriting transaction records within six blocks. The attacker was a small AI project called Qubic, which at one point controlled 52.7% of Monero’s total hash power—bringing Monero closer to destruction than at any point in its 11-year history.

Qubic has since declared that its next target is Dogecoin, another PoW-based cryptocurrency best known as Elon Musk’s favorite. The entire situation is still unfolding. This article takes you inside the attack, exploring who Qubic is, why it launched the assault, and whether Bitcoin—which also relies on PoW—is truly safe.

Moonlighting Miners

In May this year, Qubic introduced the concept of Useful Proof of Work (uPoW). Criticizing Bitcoin’s PoW mechanism as wasteful, Qubic argued that combining cryptocurrency mining with AI model training would be far more efficient:

“PoW mining, led by Bitcoin, consumes electricity on mathematical puzzles with no practical value. Its sole contribution is securing the blockchain. But in 2025, the idea of ‘wasting energy for security’ is outdated… Qubic wants to redefine mining. Instead of wasting computation on meaningless hashing, why not use that power to simultaneously train on-chain AI? That is the core of Useful Proof of Work (uPoW).”

Qubic isn’t giving miners “two paychecks for one job” so much as offering a side hustle.

Training AI models usually happens in batches, not as continuous full-load computation. After processing each batch, the system must pause to update weights and synchronize parameters. The cycle goes: peak load — idle — peak load — idle. Qubic outsources AI training tasks to people around the world. Each participant computes a portion of the data, then must wait for others to return results before moving on to the next round. Since roughly half of the computing power is left idle, Qubic decided to redirect that idle capacity into Monero mining.

At first, this seemed like a good thing! Proof of Work acts as the blockchain’s virtual fortress—the more people mining, the higher the walls. For hackers to breach it, they need even greater computing power. Whether buying machines or renting cloud servers, hash power costs money. If the target isn’t valuable enough, launching an attack simply isn’t worth it.

Qubic’s entry initially looked like a boon, but it quickly spiraled into the most severe security crisis in Monero’s history. The turning point came with an announcement in June.

Launching the Attack

In that announcement, Qubic declared it aimed to make its token, QUBIC, the most profitable coin of 2025. The plan: split Monero mining revenue—half as miner rewards, and the other half to buy back and burn QUBIC. With lower circulating supply, people expected the token price to rise. This promise lured many Monero miners to defect, switching to Qubic’s mining pool to earn QUBIC, which they believed had stronger upside potential.

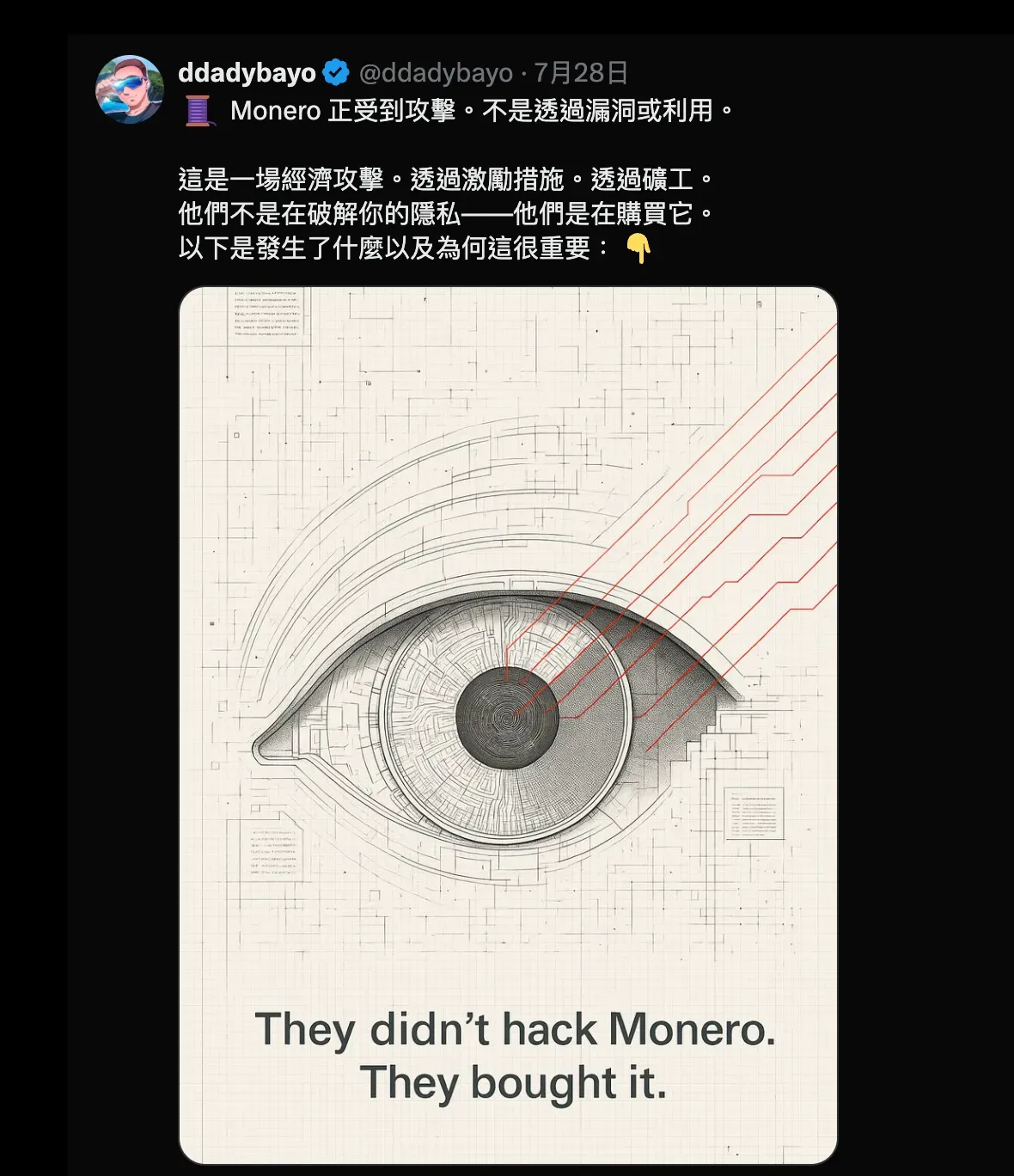

The community didn’t take it seriously at first. But by late July, a user raised the alarm: Qubic had attracted as much as 30% of Monero’s total hash power in just two months, briefly becoming the world’s largest Monero mining pool. That user stressed this wasn’t a software bug but an open, deliberate economic attack. Qubic wasn’t breaking Monero’s privacy features—it was trying to outright “buy the blockchain.”

Qubic’s Power Grab

Qubic was quick to clarify that it had no intention of harming anyone. But intentions don’t matter—the reality was clear: extreme concentration of hash power is the greatest risk to any blockchain. Once control surpasses 51%, Qubic could effectively become the blockchain’s “general secretary,” with the authority not only to decide which transactions make it on-chain, but also to launch double-spending attacks (spending the same funds twice), potentially crashing the coin’s price overnight.

The Monero community scrambled to devise defense plans. Some began monitoring Qubic’s hash rate and urging miners to leave, while others discussed the possibility of a hard fork. But major decisions require community consensus. Qubic, on the other hand, was far more agile.

Seeing that the Monero community remained uncooperative, Qubic dropped the pretense altogether. It issued a new announcement declaring it would launch a “drill” to test Monero’s ability to withstand a 51% attack. The reversal was breathtakingly swift. Qubic even held an internal vote deciding that, if successful, it would monopolize all block validation rights. That would mean Monero was no longer decentralized—while hash power was nominally distributed across different machines, Qubic would hold absolute control.

Unlike typical hackers who strike by surprise, Qubic telegraphed every move in advance—discussing, voting, and publicly announcing each step. Ironically, this transparency only added more pressure on the community.

Not every miner cares about decentralization; economic incentives are what shape consensus. The community’s calls for miners to leave Qubic had little effect because mining through Qubic was simply more profitable. The situation deteriorated further. Seeing the moment was ripe, Qubic’s founder—known by the pseudonym Come-from-Beyond—announced on August 11 that the attack would commence. He warned that over the next 24 hours, Monero’s network resilience would be tested, and while some turbulence was expected, holders should not panic. The atmosphere was one of an approaching storm.

Twenty-four hours later, Qubic declared victory. It not only gained control of 51% of the hash power but also used this privilege to roll back Monero’s blockchain by six blocks (about twelve minutes), rewriting history in the process. It even orphaned 60 blocks mined by others, rendering their efforts worthless. No wonder Qubic boasted that a project with only a $300 million market cap had subdued Monero, a $6 billion giant.

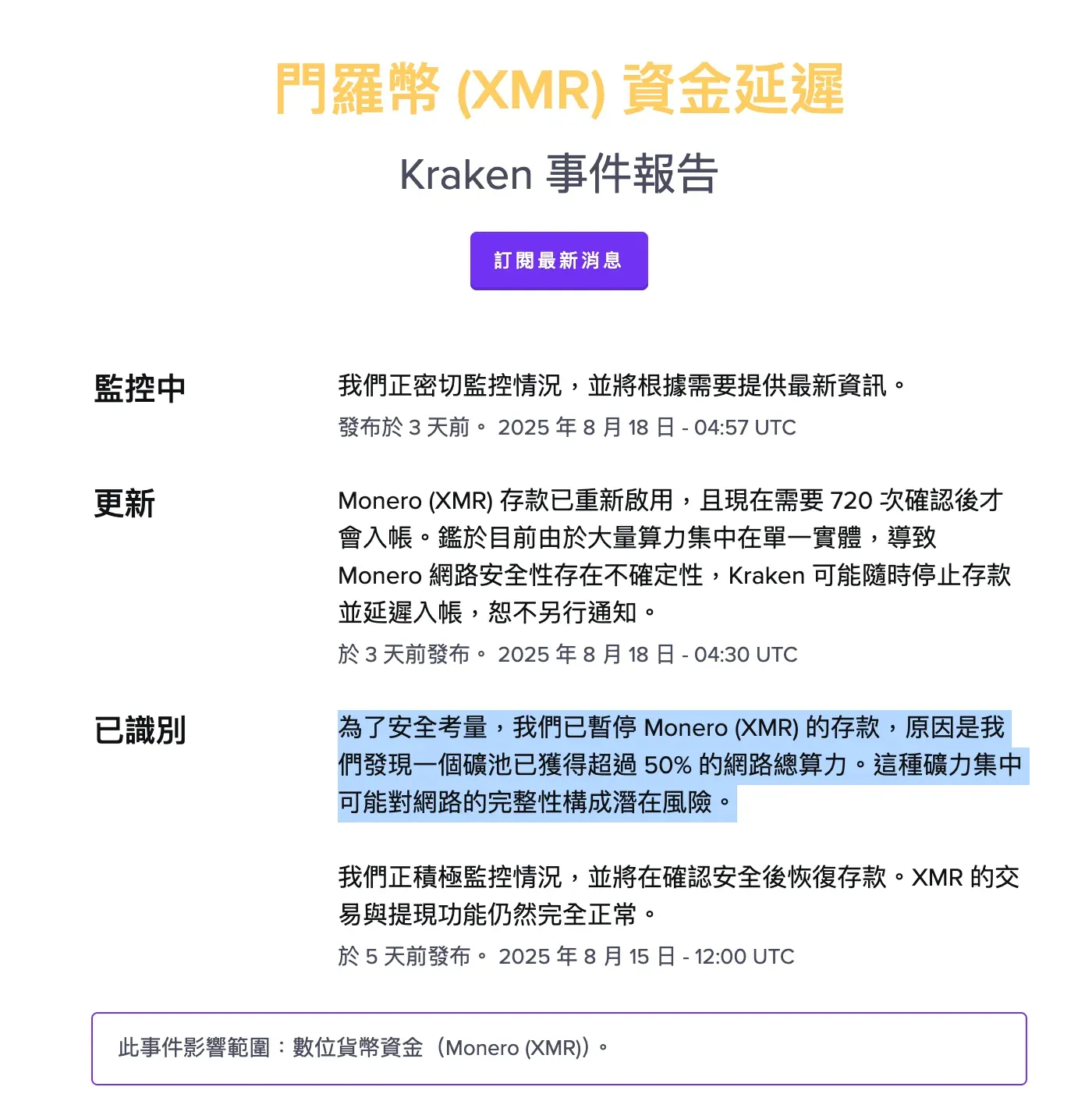

The attack prompted immediate action. Kraken temporarily disabled Monero deposits, citing the risk of a single entity controlling the blockchain, to protect its users from being affected. Ledger’s CTO also issued a warning, advising Monero holders to beware of 51% attacks and to wait longer before trusting that a received transaction was final—otherwise, they risked delivering goods only to see the payment erased and rewritten.

When everyone braced for worse, qubic backed off. Just as many feared the offensive would escalate, Qubic suddenly announced it would not launch further attacks on Monero—claiming that, after internal discussion, it concluded such actions might affect Monero’s price. How considerate! By then, however, Monero holders were already terrified, with the coin’s price plunging 33% over the span of several days. While some in the community did strike back with DDoS attacks against Qubic’s infrastructure, the damage comparison was stark: Monero had essentially taken the blows without being able to retaliate.

Qubic, meanwhile, began preparing its next wave of attacks. In addition to the already-targeted Dogecoin, other Proof-of-Work blockchains such as Kaspa and Zcash were placed on its list. Even though the Monero community later presented evidence suggesting Qubic’s claimed 51% attack was exaggerated or outright fabricated, most people cared about a different question: if PoW blockchains were at risk, was Bitcoin still safe?

Bitcoin’s Balance of Terror

The conclusion: Qubic poses no threat to Bitcoin. The real reason is a bit awkward—Bitcoin mining is no longer a decentralized network open to everyone. Instead, it has become a highly centralized industry. And paradoxically, this centralization is the very foundation of Bitcoin’s security.

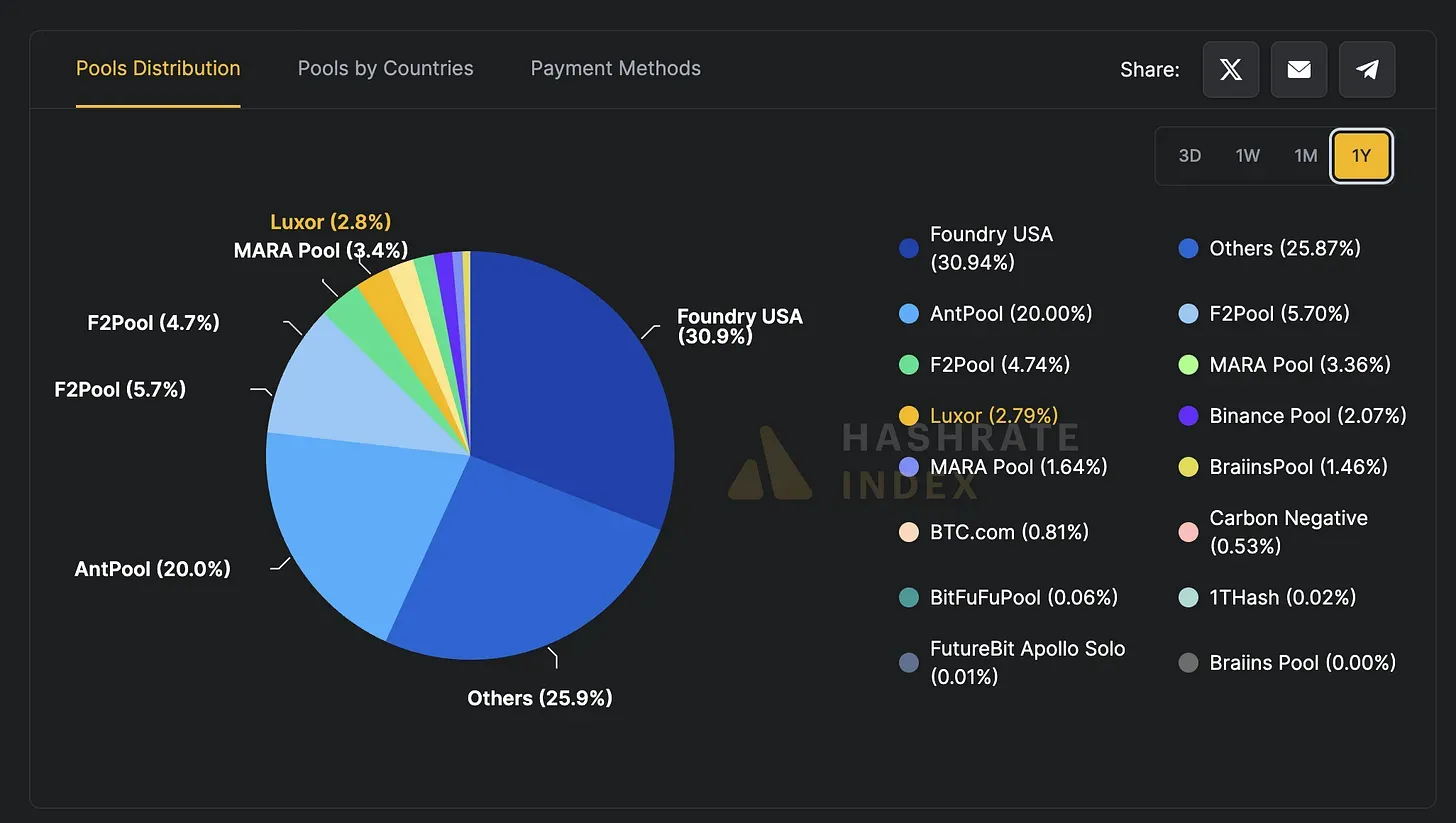

Looking at today’s hash rate distribution, the top two mining pools—Foundry USA (30.9%) and AntPool (20%)—together control over half the network’s hash power. Add F2Pool and MARA into the mix, and the top four mining pools command nearly two-thirds of global hash power. In other words, Bitcoin’s security does not rest on wide distribution but on a “balance of terror” upheld by a few mining giants. The community, in turn, tacitly accepts these large pools as gatekeepers whose economic interests align with everyone else’s.

This is a kind of prisoner’s dilemma. Large-scale Bitcoin miners must pour massive capital into purchasing ASICs, hardware that is effectively scrap metal if not used for Bitcoin mining. These sunk costs tie miners’ interests directly to Bitcoin’s security. Combined with Bitcoin’s trillion-dollar market cap, the cost of “buying out the entire chain” would be astronomical. So, while a 51% attack is theoretically possible, in practice it offers almost no incentive.

Monero, by contrast, is closer to the ideal of a decentralized blockchain. It bans specialized ASICs and only allows mining with CPUs so that anyone can participate. But precisely because CPUs are versatile—easily rented or redirected—Qubic was able to exploit economic incentives to quickly rally vast amounts of mercenary hash power and launch an attack against Monero. The result is somewhat ironic: Bitcoin’s centralization acts as its safeguard, while Monero’s decentralization became its fatal weakness.

This incident revealed that crippling a blockchain with a $6 billion market cap is not as difficult as people once imagined. Some argue the root problem is Monero’s “security budget” being too low—the number of coins issued to miners is limited, and with its relatively modest price, Qubic found an opening. Yet raising the security budget is tricky. Issuing more tokens leads to inflation that suppresses price, while market value itself cannot be dictated purely by technology.

Near-successful attacks are often the most valuable. They expose weaknesses without causing irreversible damage. While I don’t fully endorse Qubic’s methods, the outcome did resemble a stress test. If a network withstands the assault, its credibility grows stronger; if not, the community at least has an early chance to patch vulnerabilities.

Mining, after all, is the blockchain’s economic fortress. Unlike technical bugs, which can be exploited once discovered, its defenses can only be breached through economic means. But with advances in technology, the speed at which hash power can be mobilized is accelerating. Proof of Work—once seen as the blockchain’s guardian—has become increasingly vulnerable to new forms of economic incentives. Qubic’s attack laid this weakness bare.

Those insisting the attack “never really succeeded” are simply denying reality. The process already showed that decentralized communities are nearly powerless when confronted with fast-assembling economic attacks. If Monero’s community only rushes to refute criticisms instead of confronting the issue head-on, then Qubic may just be the first challenger to come knocking.