LOL! Is a Convenience Store Pickup App Seriously Part of the National Digital Infrastructure?

Taiwan ranks second in the world—behind only South Korea—in convenience store density. The sheer breadth of services they offer has led people to jokingly call convenience store clerks “the strongest species on Earth.” They not only brew coffee, boil tea eggs, and make ice cream, but also double as warehousing and logistics staff and frontline banking tellers. When elderly customers can’t figure out how to use an app or an in-store kiosk, clerks even have to step in as impromptu tech coaches to save the day.

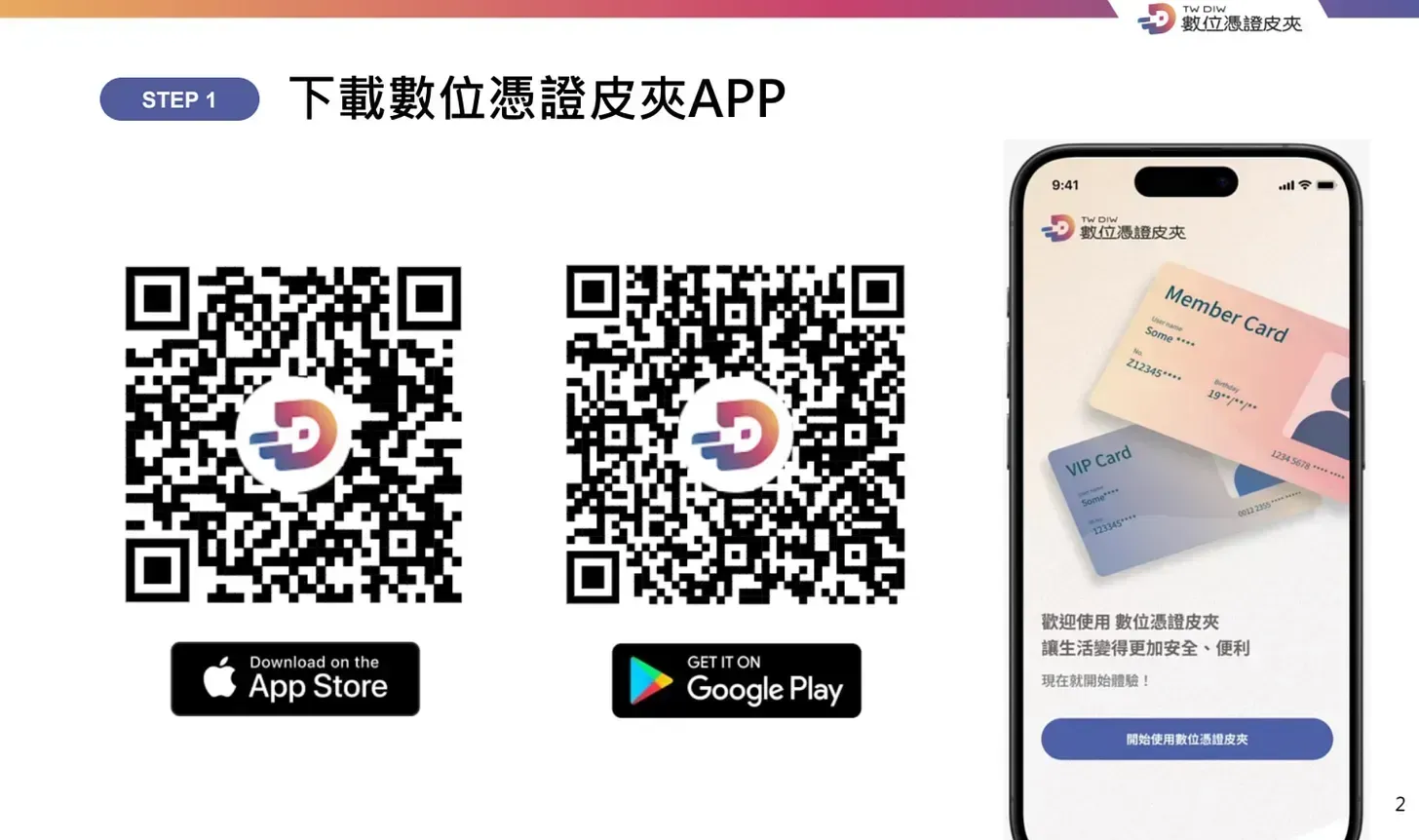

Recently, they’ve been assigned yet another new task: supporting the launch of digital credential wallet apps.

Convenience Store Pickup App

In the future, if people go to a convenience store to pick up a package but forget to bring their ID, they will still be able to collect it successfully by simply presenting a QR code within an app.

According to a press release from the Ministry of Digital Affairs:

People often need to present various forms of identification to verify their eligibility, which also raises concerns about personal data leakage. To address this, the Digital Credential Wallet adopts “selective disclosure” technology, allowing citizens to provide only the necessary information. This truly implements privacy protection under the principle of “give only what should be given—nothing more.”

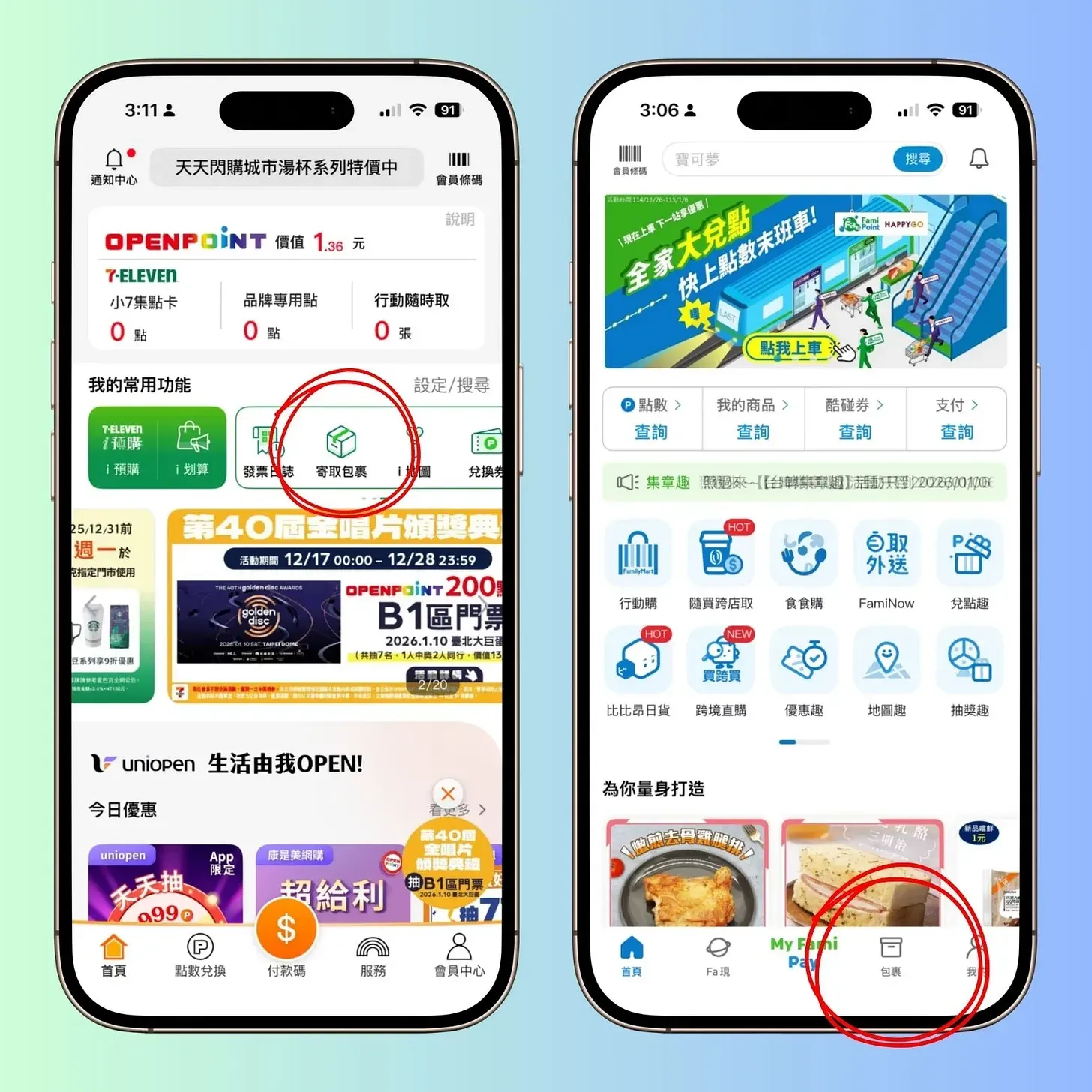

At the press conference, a variety of application scenarios for the “Digital Credential Wallet” were demonstrated. Among them, the “convenience store pickup” service—one of the services most closely integrated into daily life—has already been launched by the three major telecom operators and FamilyMart. 7-ELEVEN is expected to join on December 24, rolling out trial operations nationwide.

Even for first-time users, the entire process consists of just two steps: adding a credential and presenting it. Citizens must first obtain a credential from one of the three major telecom operators, and then use it to pick up packages at the two major convenience store chains. Despite this seemingly straightforward use case, many netizens couldn’t help but criticize it as a waste of public funds.

The reason is that both FamilyMart and 7-ELEVEN apps have long included built-in pickup functions, and Shopee’s store pickup service even works with nothing more than a phone number and a pickup code. Critics therefore question why the Ministry of Digital Affairs needs to spend taxpayers’ money to rebuild a feature that convenience stores already have.

Let me first say a word in defense of the Ministry of Digital Affairs. In the past, you had to download two different convenience store apps; now, one app is enough to handle everything. The government is saving you phone storage space—isn’t that value obvious enough?!

That was pure sarcasm. In reality, the criticism from netizens is quite reasonable and accurately points out the shortcomings in the Digital Credential Wallet’s go-to-market strategy. I call it a “resource-wasting radio”: when a computer can only be used to listen to broadcasts, you can hardly blame people for thinking it’s just an expensive, power-hungry radio.¹

The Digital Credential Wallet is that “computer.” Although car rentals, job applications, and visitor management are all potential use cases, at this stage the only scenario people can actually experience firsthand is convenience store pickup. It’s therefore unsurprising that many question why the government is spending so much money on it.

Some netizens go even further, arguing that apps like this will ultimately never be more convenient than simply showing a physical ID. This hits on another reality everyone already knows—privacy alone can’t put food on the table.

Privacy Is a Side Dish

Most people won’t download an app purely for the sake of privacy; otherwise, privacy-focused services like Proton Mail wouldn’t have long remained far behind Gmail in market share. By the same logic, even though the Digital Credential Wallet emphasizes “selective disclosure,” for most people the real main course is being able to go out without carrying physical IDs—privacy is just a bonus.

Unfortunately, in recent years people have already been bombarded by government apps for tax filing, receiving funds, getting vaccinated, and more. As a result, most people have little enthusiasm for “yet another government app.” That’s why some are asking why Taiwan can’t simply follow Japan’s example and put digital credentials directly into Apple Wallet or Google Wallet instead.

In its FAQ, the Ministry of Digital Affairs gives a rather implicit answer:

Apple Wallet and Google Wallet are primarily used for mobile payments and ticket management, with relatively limited functionality. The Digital Credential Wallet, by contrast, is a platform for managing digital credentials and data. It is open source, domestically developed, and government-governed, and should therefore be one of the service options available to the public. At the same time, Apple and Google are gradually opening their wallet services to accept national credentials, and we are also studying the possibility of compatibility.

Put plainly, this comes down to an issue of sovereignty: if digital identity were handed entirely to foreign companies to manage, how much room for autonomy would the government have left?

What the Ministry doesn’t say outright is that it, too, hopes digital credentials will one day be smoothly integrated into Apple and Google Wallets. But before that can happen, Taiwan must first establish its own set of rules for managing digital credentials. Otherwise, when Apple’s or Google’s governance mechanisms conflict with domestic requirements, whose rules should prevail?

At first glance, the Digital Credential Wallet looks like just another app. In reality, the rules behind it are the core issue²: who is allowed to issue credentials, who can verify them, under what circumstances they can be revoked, and how all of this can be done without sacrificing privacy. The design of such systems is precisely the part that no country can afford to leave entirely to a single platform.

For most citizens, however, concepts like privacy and sovereignty are abstract. Ideas such as user-controlled data or decentralized digital identity (DID)—often framed as “progressive values”—feel even further removed from everyday life. What people can immediately perceive is whether something is easy to use and whether it actually solves problems. For the Digital Credential Wallet to break out of its echo chamber, it must first expand its range of real-world use cases.

Reasonable Disappointment

The best way to prove that a computer is not just a radio is not to boast about how powerful its CPU is, but to open games, a web browser, and a calculator—showing that it can do more than just one thing. Likewise, if people are to truly understand the purpose of the Digital Credential Wallet, the Ministry of Digital Affairs must present more tangible, real-world use cases.

I suspect the Ministry still has plenty of good cards in hand. After all, the first wave of pilot partners—the three major telecom operators and the two major convenience store chains—are not government agencies themselves. If future use cases were to include digital diplomas (for job applications), a digital driver’s license (for roadside checks), or a digital health insurance card (for medical visits), the public would begin to realize that this is not merely a convenience-store pickup app, but a portable, all-purpose credential wallet. Best of all, you get convenience bundled with privacy.

I once participated in an expert consultation meeting for the Digital Credential Wallet, so I understand how difficult it is to coordinate across ministries. Take the Ministry of Health and Welfare as an example: even the digital health insurance card it has promoted for years is still far from universal, with many clinics not supporting it—let alone cross-ministerial integration. It’s therefore no surprise that some of the sharp-tongued online criticism hits the mark. After all, a tool branded as part of the “National Digital Infrastructure 3 4 5” currently offers only a single use case, which is hard to justify.

Ideally, an app would launch with two or more application scenarios from day one, making its value self-evident. But if that would significantly delay the timeline, I would rather see the first use case fully validated first, and then gradually bring additional applications online. The criticism from the public reflects reasonable disappointment. That said, as the country with the world’s second-highest density of convenience stores, perhaps turning a convenience-store pickup app into a piece of national digital infrastructure isn’t entirely off the mark after all.

1 Year-End Review 2021: The Internet Is Not a Radio, and Blocktrend Is More Than Just a Media Outlet

2 WWDC 2025’s Hidden Highlight: How Apple Ended the Era of Rephotographing ID Cards in 10 Seconds