International Scam Syndicate Mysteriously Hacked — U.S. Authorities Remotely Seize 127,000 Bitcoins, Setting a Historic Record

GM,

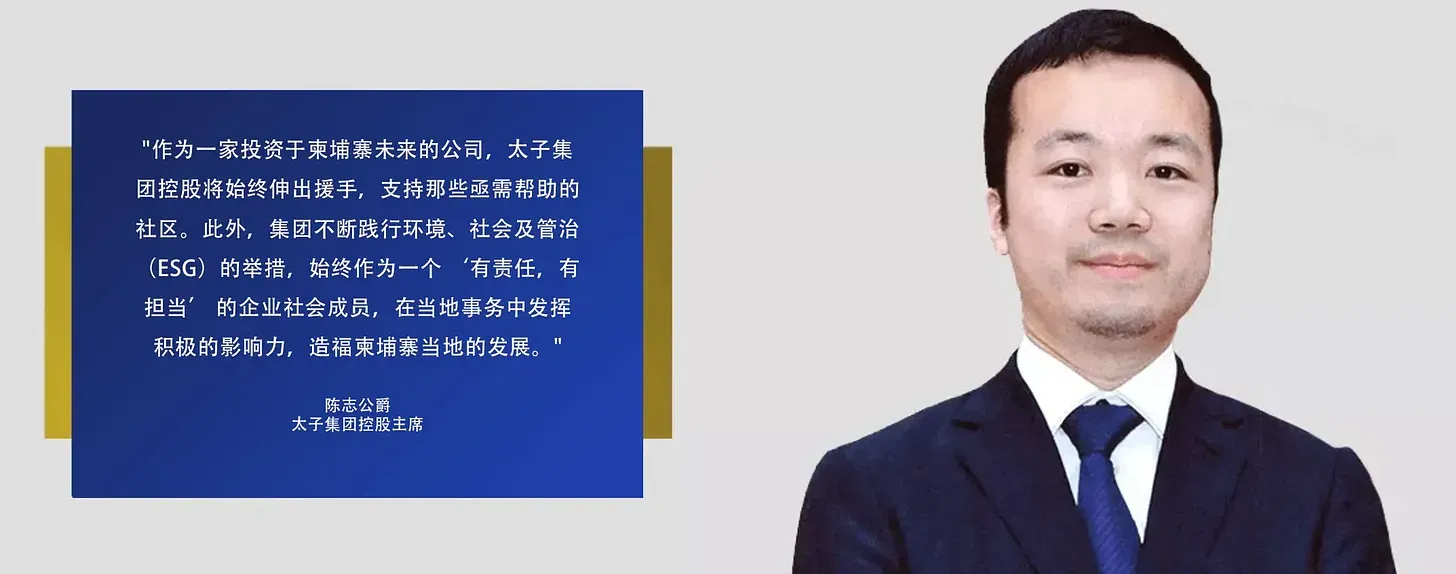

Last week, the U.S. Department of Justice announced the indictment of 38-year-old fraud ring leader Chen Zhi (English name Vincent) and seized 127,000 bitcoins from his wallet — worth around $15 billion USD — marking the largest cryptocurrency confiscation in U.S. history. The Prince Group, chaired by Chen, has been designated a transnational criminal organization, and financial institutions are now prohibited from doing business with it.

The case has sparked widespread discussion in Taiwan. Chen reportedly entered and exited Taiwan more than ten times, operated a money-laundering front company located right beneath pop star Jay Chou’s residence, and even rented office space in Taipei 101.

Chen Zhi remains at large — and most likely, not short on money. According to on-chain data, another of his personal wallets still holds nearly 16,000 bitcoins, worth around $1.7 billion USD.

If Chen hasn’t been caught, then how did the 127,000 bitcoins get seized? The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) declined to disclose details. Some speculate that the U.S. government may have secretly cracked Bitcoin’s security mechanism, though others believe the issue lies with the wallets used by the fraud syndicate.

In this article, drawing on the DOJ’s indictment and cybersecurity experts’ research reports, Blocktrend will help you understand how this transnational scam network laundered its funds, and how U.S. authorities managed to gain control of Chen’s bitcoins even before arresting him.

The “Pride of Cambodia”: Prince Group

Chen Zhi was born in 1987 in Fujian, China. According to the website of DW Capital, his Singapore-based fund management company, Chen is described as a “business prodigy” who began helping his family’s business in Shenzhen before the age of three, and later launched his first venture — an internet café — in Fujian. In 2011, at just 24 years old, Chen moved alone to Cambodia to enter the real estate market, founding the Prince Group, which became the turning point of his life.

In less than a decade, “Prince” became a household name on Cambodia’s streets. Its business empire spanned luxury residential towers in Phnom Penh, supermarkets, large shopping malls, Prince Bank, and even a watchmaking brand. In 2022, then–Prime Minister Hun Sen presented 25 limited-edition watches to ASEAN leaders — all designed and produced by Prince Horology. This gesture reflected the prestige and influence of the Prince Group in Cambodia.

Chen Zhi himself maintained close ties with the Cambodian government. He once served as an advisor to the Ministry of Interior and, in 2020, was even granted the title of Duke — the highest honor awarded to entrepreneurs by the Cambodian government. Yet just last week, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) accused the so-called “Pride of Cambodia,” the Prince Group, of being a massive fraud syndicate, naming Duke Chen Zhi as the ringleader behind it. The revelation shocked many across Asia.

Fraud and Money Laundering Network

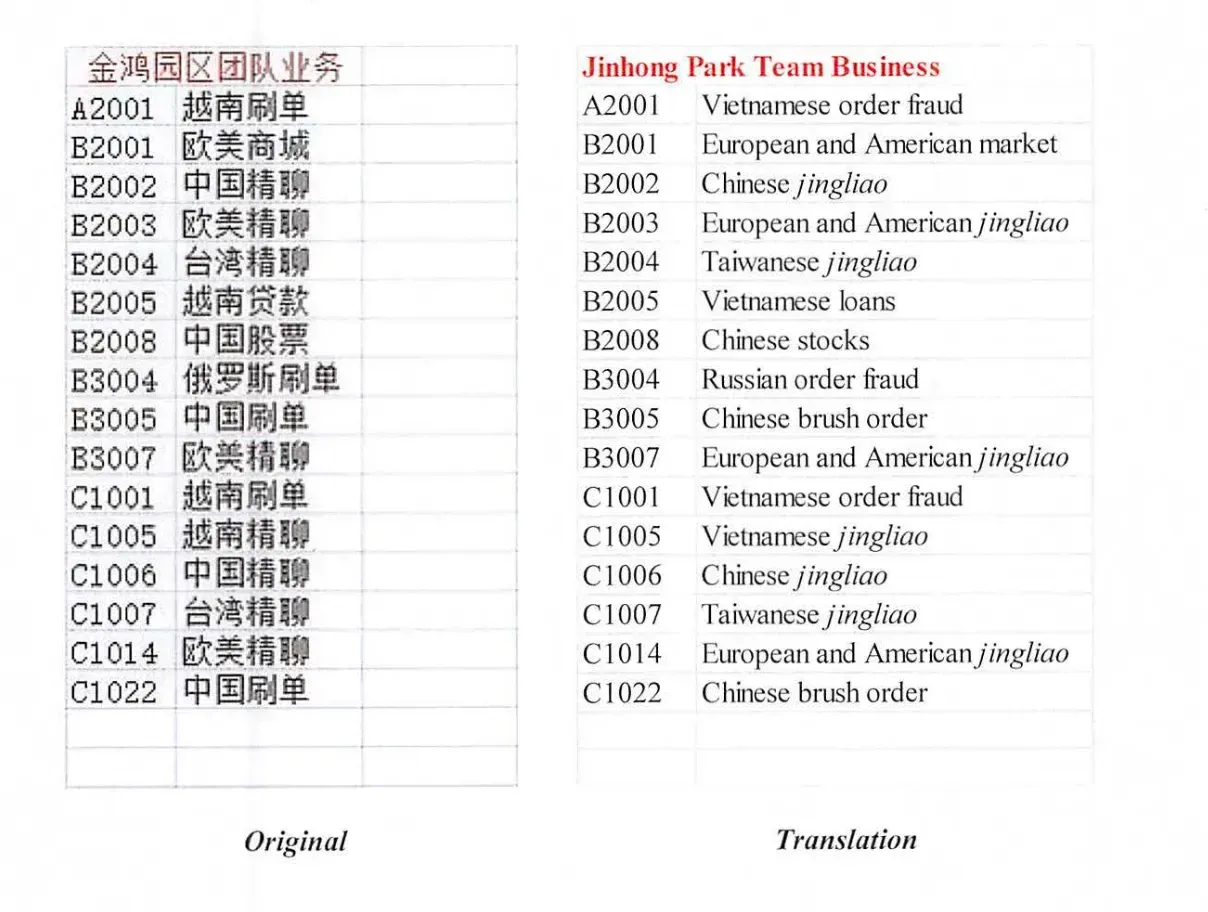

According to the DOJ indictment, the Prince Group operated under the guise of a legitimate conglomerate, while in reality running an extensive fraud and money-laundering network across Southeast Asia. The organization’s funds came primarily from online scams, illegal gambling, and fraudulent investment platforms.

The group established multiple “technology parks” along the borders of Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar, recruiting foreign job seekers with fake employment offers. Upon arrival, these individuals had their passports confiscated, were forced to participate in scam operations, and often subjected to violence.

Inside these compounds, workers carried out what the organization internally called “refined chatting” — better known as pig-butchering scams. Using social media, scammers would forge romantic or friendly relationships with victims abroad, gradually build emotional trust, and then lure them into transferring money into fake investment schemes. Once funds were received, another division of the syndicate took over to launder the proceeds.

The U.S. government’s aggressive intervention this time was not only because many Americans were among the victims, but also because the Prince Group had extended its money-laundering operations into the United States, directly crossing an American law enforcement red line.

To avoid bank risk controls and anti-money-laundering alerts, the Prince Group set up shell companies in the United States to receive funds. These firms ostensibly provided “marketing services” or “consulting,” but in reality they functioned as intermediaries for scam proceeds. The money was first disguised as legitimate commercial transactions, then converted into Bitcoin via over-the-counter (OTC) trades and quietly moved abroad.

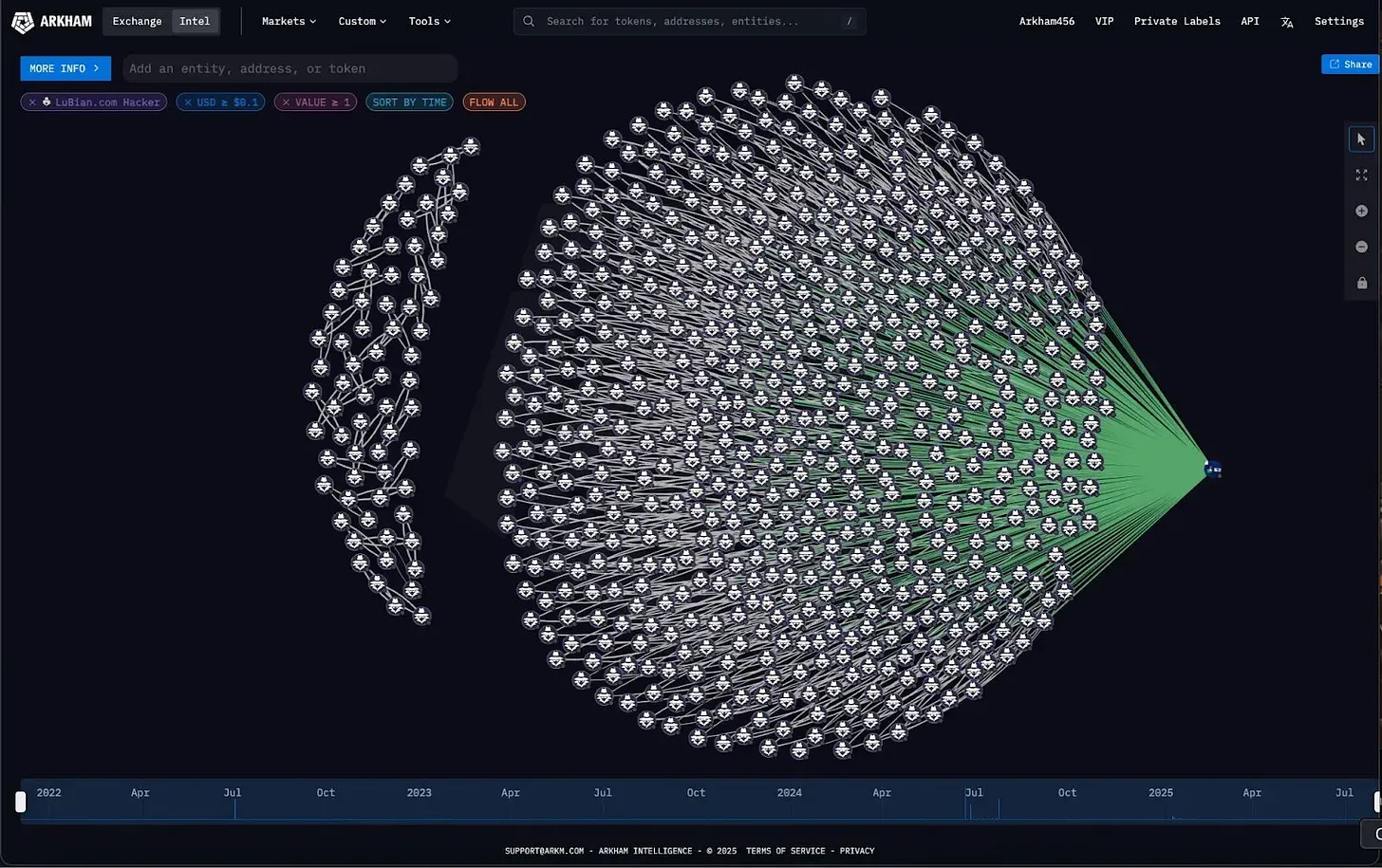

Many people assume that once money is converted into crypto it’s safe—but the Prince Group clearly had expert guidance. Crypto flows aren’t “encrypted”; they’re recorded on a public ledger anyone can inspect. Aware of this, the group designed a highly elaborate on-chain laundering process to evade tracing, broken into three stages: spray → funnel → mining-based laundering.

First comes spraying. The syndicate “sprays” large sums of crypto into thousands of tiny transactions, dispersing funds across many addresses and repeating the process over multiple layers. Even with the most advanced tracking tools, investigators see only a tangled web of transfers, making it hard to map direct relationships between addresses.

Next is funneling. After some time, those small amounts are gradually consolidated back into a handful of primary wallets. The longer this delay, the harder it becomes to reconstruct the original money flows.

The final stage is where the real masterstroke happens. The Prince Group simulated legitimate business activity by transferring small amounts of crypto into its own mining operation—Lubian.com, which at one point ranked as the world’s sixth-largest Bitcoin mining pool. Through Lubian’s profit distribution and internal accounting processes, the group mixed illicit funds with clean ones. To outside observers, the money appeared indistinguishable from miners’ legitimate earnings. Even when deposited into regulated exchanges, it wouldn’t trigger risk controls. In this way, funds obtained through fraud were effectively laundered into “clean” money.

But in late 2020, an unexpected twist struck the group’s money-laundering operation—a mysterious theft.

The Mysterious Heist

On-chain data shows that more than 100,000 BTC were transferred out of Lubian’s wallets over just a few hours. Although every transaction was recorded on-chain, no one knew what had actually happened. There were no media reports, no police complaints. Most people assumed the outflows were related to China’s crackdown on Bitcoin mining, believing Lubian was simply shutting down operations.

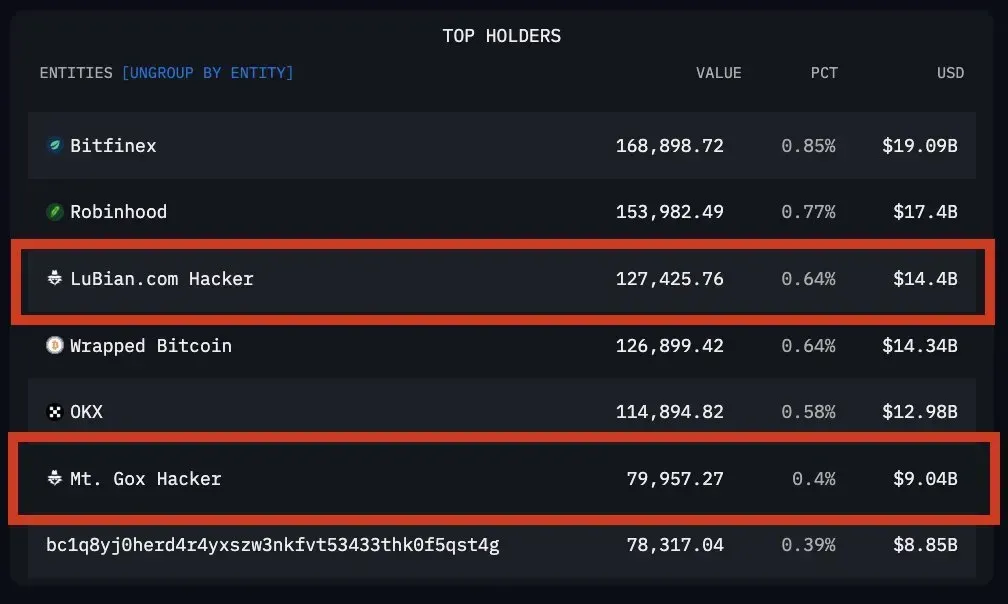

It wasn’t until five years later that the mystery resurfaced. Analysts began to suspect that this was one of the largest overlooked Bitcoin thefts in history. In August this year, blockchain analytics firm Arkham released a report confirming that Lubian had indeed been hacked, losing 127,000 BTC—funds that remain untouched in the hacker’s original wallet to this day.

Despite the staggering amount—worth tens of billions of dollars and even surpassing 1 the infamous Mt. Gox hack of 2014—most people still regarded it as just another unresolved crypto cold case.

It wasn’t until last week that the mystery finally unraveled. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) unsealed its indictment against Chen Zhi, announcing that it had successfully seized 127,000 BTC. Upon closer inspection, people realized that the wallet address listed in the DOJ’s official statement was the same “hacker wallet” from 2020. Overnight, the entire narrative flipped. Could it be that the U.S. government itself was the hacker who infiltrated Lubian in 2020? Or had they already identified the hacker and quietly taken control of both him and the stolen funds?

At present, only the U.S. government knows the hacker’s true identity. But according to cybersecurity experts, the issue did not lie in Bitcoin’s underlying protocol — it stemmed from a vulnerability in Lubian’s wallet software caused by insufficient randomness.

The Cracked Private Key

Strictly speaking, the hacker didn’t steal the private key — he calculated it. Using brute-force mathematics, the attacker computed the exact same private key as Lubian’s wallet, then transferred the coins away.

In theory, a wallet’s private key should be derived from “cosmic-level randomness,” making it practically impossible for any existing computer to reproduce within a human lifetime. However, the random number generator (RNG) used by Lubian’s wallet software might have been shockingly weak — perhaps just picking a number between 0 and 4.2 billion. While that may sound vast, a hacker equipped with a few GPUs could exhaust all possible combinations in a single day.

A similar incident occurred in 2022, when the popular Trust Wallet browser extension first launched. Developers had used a random number algorithm originally designed for game prize draws to generate wallet keys. As a result, hackers didn’t need to breach servers or deploy phishing links — they could simply iterate through all possible combinations and calculate users’ private keys, draining their funds directly. Although Trust Wallet quickly patched the flaw, any user who had created a wallet before the fix was essentially leaving their assets behind an unlocked door.

The cybersecurity research collective Milk Sad believes that Lubian made a similar mistake years ago — using an algorithm with insufficient randomness when generating wallets, which made all private keys predictable. In other words, the hacker didn’t need to penetrate Lubian’s internal systems; they could simply use the same flawed algorithm to calculate the private keys.

This means the real problem lay in the wallet software itself. Traditionally, crypto thefts happen because an exchange is hacked or a user loses their private keys. But in Lubian’s case, no data was lost — the coins simply vanished into thin air. To outsiders, there seemed to be only one explanation: Bitcoin itself must have been hacked.

In reality, no matter how carefully users guard their private keys, if the original randomness used to create the wallet wasn’t truly random, hackers can eventually compute the private key. What we assume to be astronomically impossible to guess actually has a defined boundary in computer science. What feels “impossible” to humans is often just a matter of time for computers. It’s no wonder that after the incident, several wallet companies immediately issued statements emphasizing, “Our users are not affected!”

I used to think that all wallets were more or less the same — differing only in interface and design. But after this event, I’ve become much more cautious. Wallets that are widely used, time-tested, and open source are far more trustworthy. For example, if something went wrong with the globally popular MetaMask wallet, its massive user base would uncover it almost instantly. New wallets that look sleek and offer innovative features but have few users are best treated as “spare change wallets” for now.

Perhaps Chen Zhi himself has spent years wondering why his Bitcoin disappeared. He probably never imagined that after building such a sophisticated money-laundering network, the very thing that brought it all down wasn’t government surveillance or blockchain forensics — it was his own faulty random number generator.

1 The Missing 850,000 Bitcoins Have Returned! Why Did the World’s Largest Exchange Collapse?