Huma Finance: On-Chain Credit Lending Without Relying on Lawsuits

GM,

It’s been a while since I’ve written about a DeFi application. Recently, Solana introduced a new term: PayFi, short for Payment Financing. At first, I didn’t quite understand it—doesn’t “payment” just mean paying money? Later I realized: if a company doesn’t have the funds to pay right away but expects incoming revenue in the near future, and needs to “borrow first, pay later,” that’s essentially what PayFi is about.

The main subject of this article is Huma Finance, a PayFi lending protocol built on the Solana blockchain. Its core feature is that returns come from real-world economic activity, not from airdrops or token-driven “ponzi-nomics.” This article explains what problem Huma is trying to solve.

Accounts Receivable Financing

Let’s say I run a factory called “Mingen Screws.” Thanks to our advanced technology, even Foxconn sources screws from us to assemble the latest generation of 3C products. The only catch is: Foxconn informs us that payment will come in 90 days. But as a small factory, we still need to pay for materials every day and cover our payroll. We can’t exactly ask employees to “tighten their belts” for three months, right?

So, I take the invoice issued by Foxconn to the bank and ask for a loan. The bank knows Foxconn is guaranteed to pay, so they’re willing to lend me money at an annual interest rate of 10%. When Foxconn’s payment comes in, I repay the bank.

This is what’s known as Accounts Receivable Financing, and it's actually very common in Taiwan. Many Taiwanese small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are part of the global supply chain, serving as upstream suppliers for major brands like Apple and Tesla. However, the “ship now, get paid later” model puts pressure on smaller companies. A one-week delay in payment might mean missing payroll or failing to deliver orders. This kind of “credit-based cash flow management” is a daily survival strategy for these businesses.

“Mingen Screws” is fortunate to have a reliable, creditworthy client like Foxconn. But if the client isn’t a publicly listed company, borrowing money becomes much more difficult. Banks may not recognize the client’s name and thus question their ability to pay, which can result in lower loan-to-value ratios, higher interest rates, or even outright rejection.

No one wants to end up with bad debt—banks are managing risk, but in doing so, they sometimes turn down legitimate borrowers. This is where Huma Finance, the focus of this article, steps in. Huma provides an on-chain lending platform, offering businesses another path to access capital—by borrowing directly from Huma.

Huma Finance

According to Huma’s own description, it is a credit financing service built on the Solana blockchain, and it highlights three key features:

- Real Returns: Yields come from interest paid by borrowing businesses

- Permissionless: Anyone can provide capital and participate in the returns

- Borrower Vetting: Borrowers must be verified financial payment institutions

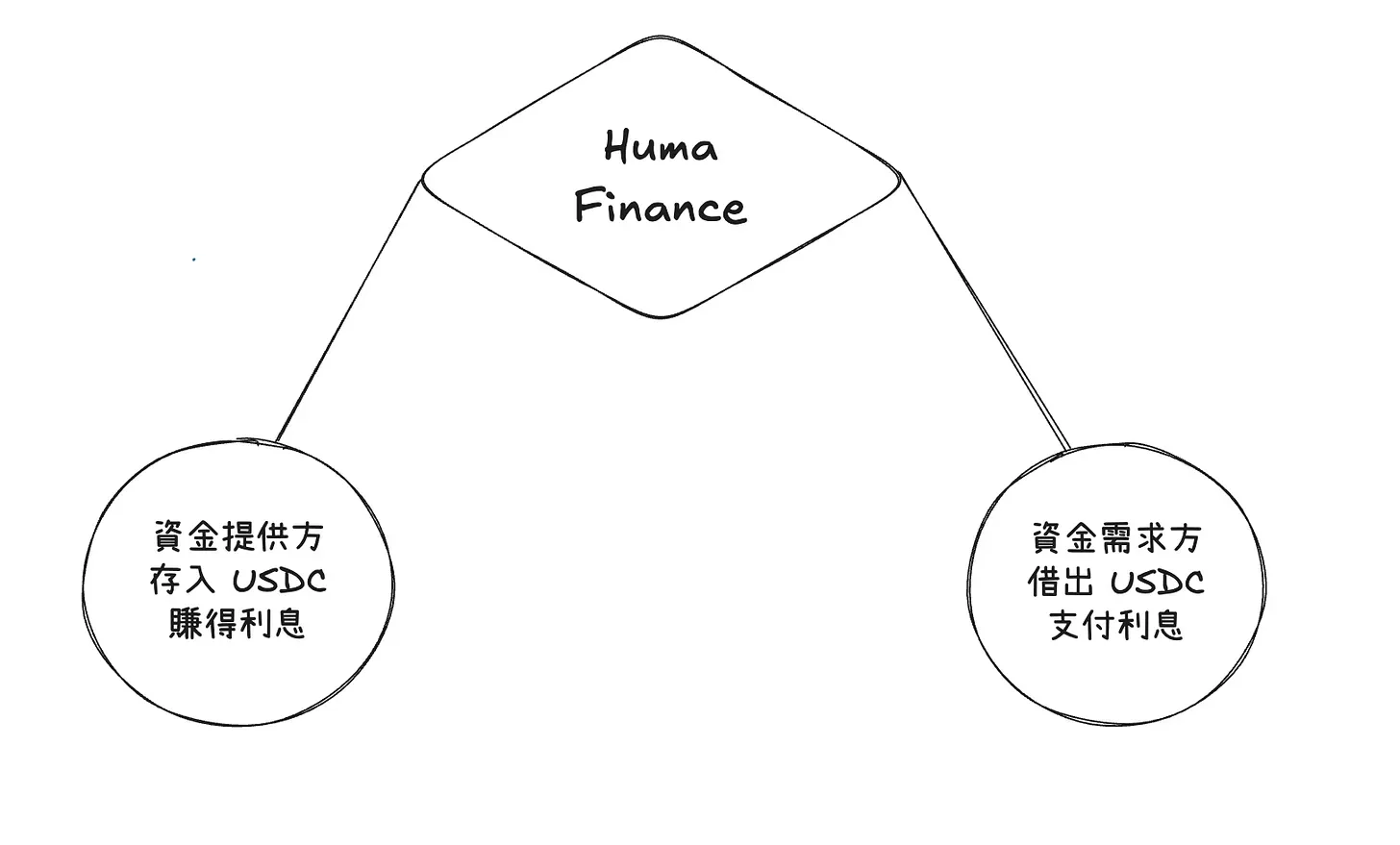

As illustrated in the diagram below, Huma aggregates capital from users on-chain, lends it out to businesses in need, and earns interest from the spread. Huma claims to have processed over $3.8 billion USD in transaction volume, consistently delivering double-digit annual yields to its liquidity providers.

Huma assumes everyone will participate as a capital provider. Users can deposit USDC on the Solana blockchain and earn an annual return of around 10.5%. The yield is fairly attractive, but the capital pool is currently full—so even if you have funds ready, all you can do is watch from the sidelines. This is a deliberate limitation set by Huma to prevent an influx of excess capital from diluting the returns. After all, it wouldn’t be able to advertise double-digit yields otherwise. 😂

Additionally, while Huma claims not to engage in the usual token games, it still plans to launch a token in the future. The “Huma Feathers” shown on the site are part of a point-based reward system. The more users invest and the longer they lock their funds, the more tokens they’ll eventually receive. The overall design is simple—but what really matters is who Huma is lending to, and what happens if the borrower defaults.

So far, Huma has gone through four rounds of lending, with the borrower in each round being Arf, a cross-border settlement platform. Understanding how Arf makes money is key to evaluating whether Huma’s claim of providing “real yield” actually holds up.

Let’s say I run a small business called “Mingen Remittance”, which specializes in helping migrant workers send money from Taiwan back to Indonesia. My customers expect their families to receive the funds the same day. But if I wait to receive the money before initiating the transfer, it won’t arrive in time. That means I need to pre-fund a pool of money in Indonesia so I can release the payment immediately once the customer pays me.

The challenge is that I don’t only serve Indonesian customers—I also handle remittances to the Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand. Pre-funding across multiple countries ties up a significant amount of capital. This is where Arf, a company well-versed in blockchain and USDC, comes in to solve my problem.

Arf fronts the money on my behalf, allowing Mingen Remittance to operate multi-country cross-border transfers without having to pre-position capital in each country. As long as I repay Arf—principal plus interest—after receiving payment from my customers, everything runs smoothly. That’s the core of Arf’s business model.

Even though Arf can move funds quickly, if too many repayments get stuck, its business growth could hit a ceiling. That’s why Arf turns to its financial backer, Huma, to borrow even more USDC.

Let’s say Arf makes an advance for just five days and immediately lends the repaid funds to the next client. In a year, it could cycle this capital up to 70 times. If Arf earns 0.3% per cycle, that adds up to a 21% annual return. After paying Huma’s 10% borrowing cost, Arf still pockets 11% in profit. This is why Arf is willing to borrow at relatively high interest—it benefits from fast turnover and effective risk control, making the deal worthwhile.

Traditionally, people assumed that companies borrowing on-chain were subprime businesses that couldn’t secure loans from banks. These firms would immediately convert the borrowed crypto into fiat to use. But Arf is different—it needs USDC specifically. If Arf were to borrow from a bank instead, it would face additional costs and friction when converting funds on-chain, making it less efficient and more expensive.

Now, even though Arf runs a legitimate business, what happens if one day it defaults? How does Huma ensure investor safety in that case?

What Happens in Case of Default?

Huma claims to currently have a 0% default rate, which sounds like a dream investment. But I believe that’s because the platform is still small in scale, and so far has only partnered with a single borrower—Arf—making risk easier to manage. As the platform grows and lends to a more diverse pool of borrowers, encountering bad debt will be inevitable. Risk is part of doing business—the key is identifying it early and minimizing losses.

Huma has three layers of defense:

1. Borrower Eligibility

Huma only allows borrowing by qualified institutions that have completed KYC/KYB procedures. Not just anyone can take out a loan.

2. On-Chain Transparency

Huma tracks a borrower's financial flows and borrowing history on-chain to build a decentralized credit scoring system. If there are signs of late payments or unusual repayment behavior, the borrower's credit score drops, which can reduce their borrowing limit or get them blacklisted entirely.

3. Reserve Fund Mechanism

In the event of an actual default, Huma has a reserve fund to temporarily cover returns for investors. If the loan is eventually repaid, the fund is replenished. If not, the remaining losses are distributed proportionally among investors.

It’s clear that this isn’t a risk-free investment. That’s why Huma implements a tiered system for investors. Those willing to take on more risk receive higher returns—but they’ll also be the first to absorb losses in case of defaults. More conservative investors get lower yields but are better shielded from risk.

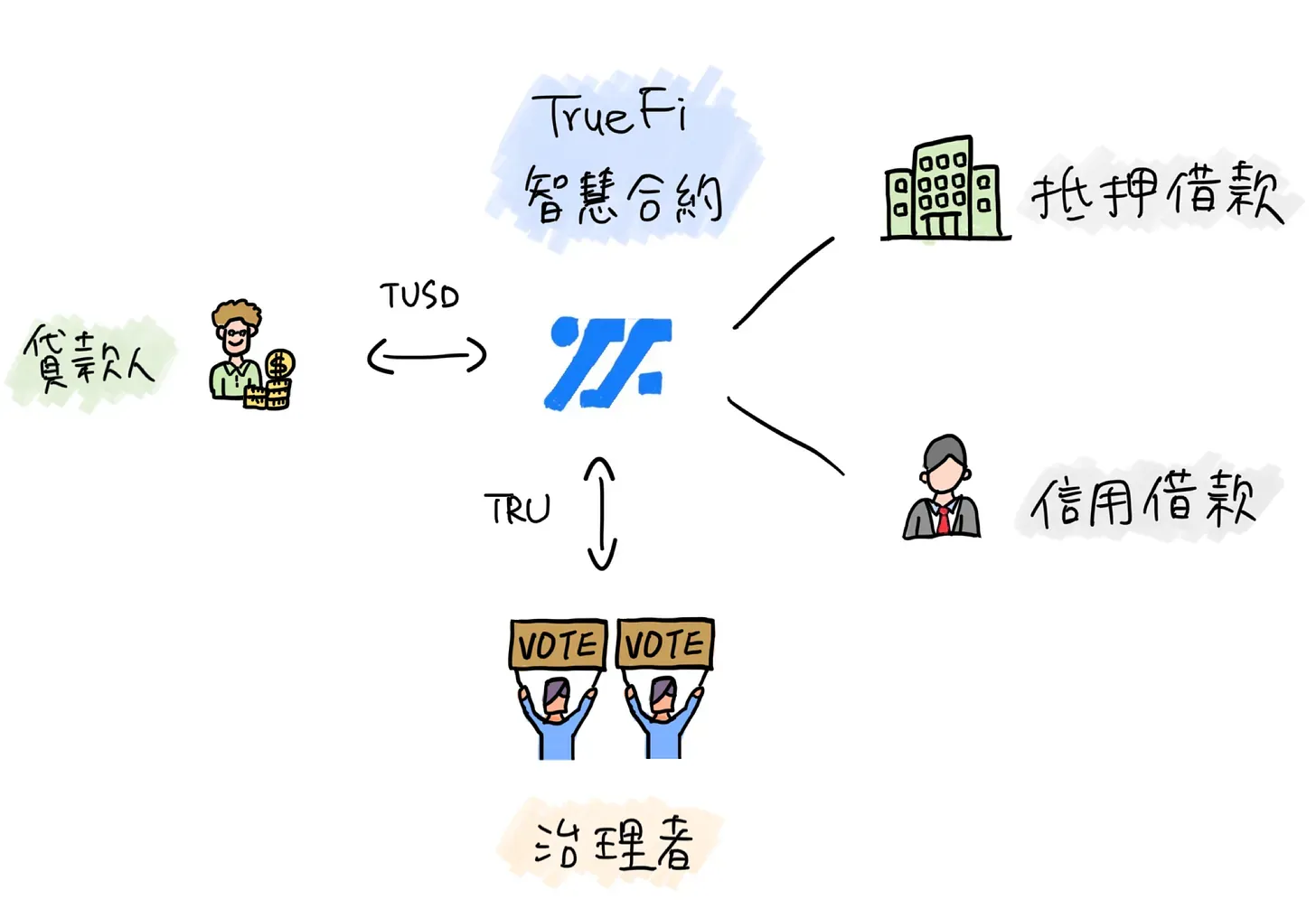

Legal action is considered only as a last resort. This is a key difference from the on-chain lending, off-chain litigation model1 introduced by TrueFi a few years ago. TrueFi proactively set aside legal budgets and initiated lawsuits immediately upon default. Huma, by contrast, deliberately places legal recourse at the very end of the process due to its high cost and uncertain outcomes. In other words, dispute resolution is baked into the product design itself. For investors, this means fewer prolonged legal battles and a clearer risk assessment at the time of investment.

If more businesses start operating on-chain and need USDC for liquidity, Huma will attract more legitimate borrowers, helping to gradually erase the stigma that “companies borrowing on-chain are just those rejected by banks.” But as of now, I personally still hesitate to participate in Huma.

That’s because, at its core, it still relies on trusting Huma’s credit evaluation of borrowers. This isn’t a transparent or objective standard—only Huma knows who qualifies for loans and who doesn’t. Huma acts as both product architectand credit assessor, playing the dual role of both player and referee. On one hand, Huma wants the model to scale; on the other hand, if loan approvals are too strict, capital might sit idle. Striking the right balance is entirely up to Huma.

Traditional financial products rely on punishment mechanisms—if you don’t repay, you face court or jail. No one wants to go to prison, so people are incentivized to avoid default. But decentralized finance has no teeth; cross-border litigation is costly and complicated. Instead, it makes more sense to predefine how risk is shared, so participants know upfront how much they could lose in the worst-case scenario.

By turning risk into a product, where high risk corresponds to high return, defaults are no longer unpredictable catastrophes. They become a built-in part of the product design. That, to me, is the biggest innovation—and the fundamental difference between decentralized credit systems and traditional finance.