Defying the "Attract, Entrap, Exploit" Rule: Why the Ability to "Leave at Any Time" Is the Ultimate Moat

GM,

About a month ago, my wife invited me to try vibe coding together to build a family expense-tracking tool. Since then, I’ve fallen in love with the feeling of “making things myself.” Whether it’s slide decks for talks, registration pages for in-person courses, or even an information dashboard I built last week when a family member was suddenly hospitalized—to consolidate updates from different sources and make communication easier—I’ve been using AI to build everything from scratch.

The more I use AI, the more I find myself understanding why blockchains matter. This happens to echo a recent goal Vitalik Buterin set for Ethereum in 2026: passing the “walkaway test.” Simply put, if the developers walk away, can users still take their stuff with them? Let me start with the family expense tracker my wife and I built together.

A Family Expense-Tracking Tool

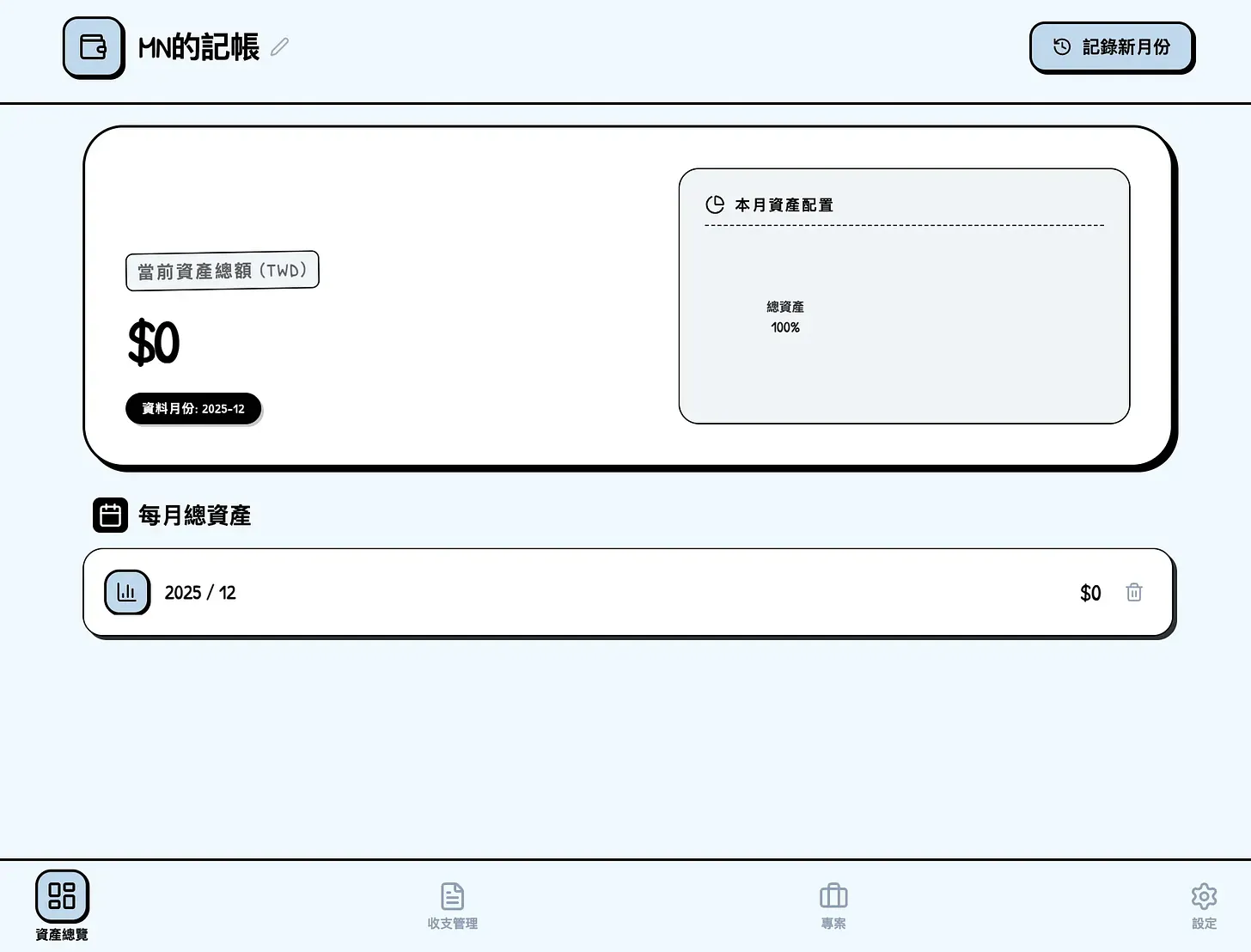

My wife has a habit of recording her monthly personal asset balances in Google Sheets so she can track them over time. I once asked her, “With so many options on the market, why not just use an off-the-shelf budgeting app?”

It turned out that the features she needs are scattered across different applications. Google Sheets may be the most bare-bones option, but it’s also the most flexible. So our goal was to build an expense-tracking service that truly fits her needs. Gemini Canvas quickly generated a beautiful front-end interface for us—but problems surfaced almost immediately.

Every time we refreshed the webpage, all previously entered data disappeared. My task then became wiring up a backend database—saving every input to Firebase so the app could retain its history.

We excitedly shared the budgeting tool with family members, only to realize that without a user account system, everyone’s records would get mixed together. Fortunately, Firebase’s built-in Authentication supports a variety of login methods, from email and password to social logins. With a front end, a back end, and authentication in place, our family budgeting service was finally complete.

That said, the tool is currently heavily dependent on centralized services. If the developer forgets to pay the bill (which I’m still a long way from doing), or if a user’s social account is revoked, the app could become unusable. That got me thinking: how do we ensure this budgeting tool can be truly “set and forget”—so that even if I suddenly disappear and no one maintains it, my family can still retain all their data intact, and even continue using it?

This is exactly what Vitalik Buterin has been advocating recently with the idea of the “walkaway test.”

The Walkaway Test

In the software world, there’s a concept known as the bus factor. It asks: if a team member were unlucky enough to be hit by a bus while walking down the street, would the entire project grind to a halt? If that person is the linchpin with outsized influence over the project, the bus factor is 1. The lower the bus factor, the more fragile the project.

The “walkaway test” simply shifts the subject from people to services. If an account disappears, a company goes under, or servers are shut down, can the product still keep running? Can users take their data with them? Vitalik Buterin argues that the ultimate goal of Web3 is to push this index as high as possible:

We want to build decentralized applications that are censorship-resistant and don’t grind to a halt just because some third-party service breaks. These applications must be able to pass the “walkaway test”—even if the original development team disappears, the service should continue to run. As a user, you shouldn’t even notice when an underlying service (such as Cloudflare) goes down; even if Cloudflare were hacked by North Korean attackers, your normal usage shouldn’t be affected. The stability of decentralized applications must not depend on any single company, ideology, or which political party is in power, while still protecting your privacy. This applies not only to finance, but also to identity, governance, and all kinds of foundational infrastructure that people want to build for civilization.

The first idea that came to mind was adding wallet login (Sign-In with Ethereum¹) to our family budgeting tool. A wallet address is derived mathematically and cannot be unilaterally revoked; as long as the private key exists, it’s unaffected by any company going bankrupt. As for the front end and back end, we could introduce the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS)² or decentralized storage like Arweave³ to improve system resilience.

Vitalik also specifically pointed out that his favorite document editor, Fileverse⁴, has already passed the “walkaway test.” Even if Fileverse shuts down, the app crashes, or the developers disappear, users can still retrieve their documents. That’s because Fileverse runs on Ethereum, stores data end-to-end encrypted on IPFS, and uses wallets as user accounts. As long as users securely keep their backup keys, they can exit via a pre-planned escape route in the future.

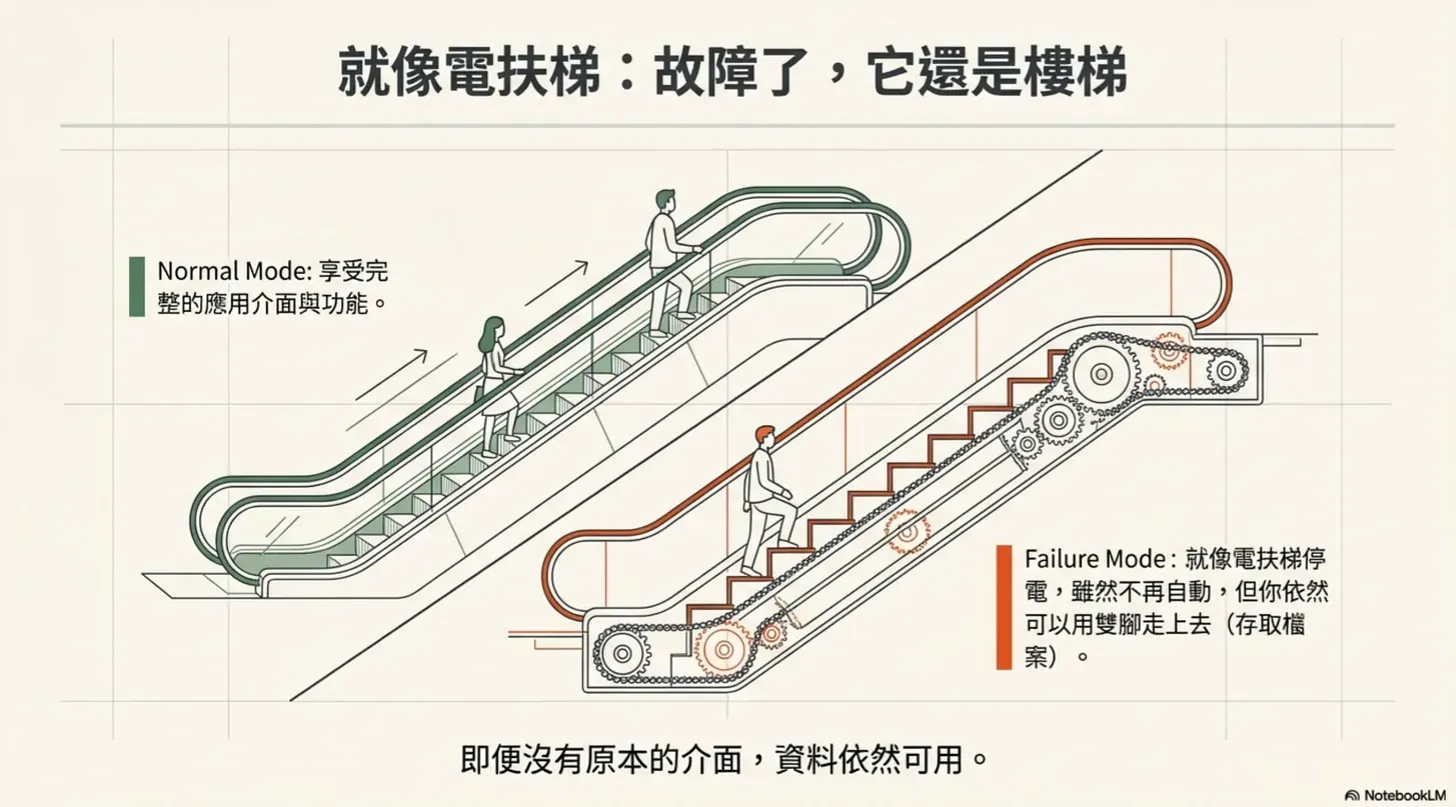

Through the recovery website, users can enter their backup key to successfully restore all their documents, then download them in PDF or Markdown format. Even without the original application interface, they can re-upload the .md files to HackMD or Notion and continue editing. It’s like an escalator breaking down—you can still use it as stairs.

Some might argue that Google Takeout or Notion can also export documents as Markdown. However, those methods rely on a single premise: the service must still be active. As long as Google or Notion is operating normally, exporting data is easy. But if you suddenly remember five years after a service has shut down that you need your files, can you still take them with you? With Fileverse, you can. This is the fundamental difference between the two.

No one wants their memories to sink along with a platform, but the real challenge is this: how do you convince an entrepreneur to let their product pass the "Exit Test"?

Choosing to Stay Because You Can Leave

The "Exit Test" contradicts the basic logic of most Web2 platforms: attract, entrap, and exploit. Look at Facebook, and you’ll see exactly how this works.

What many call a "product moat" is often just a fancy term for incompatible formats and massive migration costs. If your account is deactivated, everything vanishes instantly. Platforms are intentionally designed to make it difficult for users to leave, all to squeeze out maximum value.

To an entrepreneur, passing the "Exit Test" means you can neither trap nor exploit your users. Why go through the trouble? It’s also a hard sell to shareholders: why invest effort into pre-planning an "escape route" for users? Shouldn't you be the one monopolizing the data, dominating the relationship, and profiting from it?

This reflects a "man over nature" worldview—the assumption that a platform can last forever. The reality is quite the opposite. Corporate lifecycles are getting shorter; who can guarantee their product will still exist in ten years? Ultimately, preparing for the "Exit Test" is like buying one's own coffin. It is a form of optimism toward the future—a willingness to bet on the long term and forego immediate returns because you know something better lies ahead.

I don’t expect this to become the mainstream mindset in the short term, but I do place an extra level of trust in products willing to implement the "Exit Test." This is because it best reflects the development team's confidence: users aren't stuck on the platform because they have no choice; they stay by choice, even though they know they could leave at any time.

- Sign-In with Ethereum: A Web3-Native Authentication Mechanism ft. Wayne Chang, Founder of SpruceID

- InterPlanetary File System (IPFS): How Web3 Tackles Cyber Wars of Attrition

- Arweave: Lessons from Apple Daily and the Library of Alexandria for the Internet

- Deep Dive into Fileverse: The Decentralized Notion Favored by Vitalik Buterin