AI Hackers Have Arrived! On-Chain Offense and Defense Enter the Hot Weapons Era

GM,

AI hackers are here—and they can launch attacks autonomously. Last week, the security research team at AI company Anthropic released a critical report showing that AI agents are already capable of independently discovering vulnerabilities in smart contract code, planning attack strategies, and executing attacks.

In a simulated environment, the AI agents trained by Anthropic “made off” with about USD 4.6 million. Because the losses were relatively small and the money wasn’t real, some immediately questioned whether Anthropic was exaggerating the threat—using fear as a marketing tactic to promote its own AI defense solutions. I don’t see it that way. This report demonstrates that in the age of AI, the nature of attacks has fundamentally changed, and legacy defense methods are no longer sufficient. To understand why, let’s start with an event from over a century ago: the Boxer Rebellion.

The Arrival of AI Hackers

In the late Qing dynasty, China was repeatedly invaded by foreign powers. When the state could no longer guarantee security, people sought alternatives. The Boxers believed that through physical training they could become immune to swords and bullets. Using close-combat, cold-weapon thinking to confront long-range, hot-weapon warfare, the result was total defeat.

AI is the digital battlefield’s version of hot weapons.

In the past, launching a hack was extremely costly. Attackers had to analyze code in advance, reason through state changes, devise attack strategies, and then wait for the right moment to strike. The entire process was time-consuming, labor-intensive, and heavily dependent on individual experience. This was the classic “cold-weapons era”: high costs, limited efficiency, and little potential for large-scale damage.

Anthropic’s report formally declares that the digital battlefield has now entered the “hot-weapons era.”

The Hot-Weapons Era

The research team used three language models—Claude Opus 4.5, Claude Sonnet 4.5, and GPT-5—to build autonomous AI hackers. These agents can operate continuously 24/7 and run multiple rounds of analysis and attempts in parallel. When they fail, they automatically adjust their strategies and keep iterating until they succeed.

To test the destructive potential of AI hackers, the researchers set up two battlefields. The first was a “digital firing range” compiled by DeFiHackLabs, which contains 405 known smart contract vulnerabilities from 2020 to 2025. The researchers gave the AI hackers 60 minutes to see whether they could identify vulnerabilities on their own. The result: across the three AI setups, they uncovered 19 vulnerabilities and successfully stole about USD 4.6 million in test funds.

But that was only the beginning. Since the AI hackers might have already encountered these cases elsewhere, the researchers took a more objective approach. They selected 2,849 recently deployed on-chain smart contracts with no known vulnerabilities and again gave the AI hackers 60 minutes to attack. This time, the AI hackers discovered two entirely new zero-day vulnerabilities and extracted USD 3,694. The total search and execution cost for the AI hackers was just USD 3,476.

In other words, AI-driven attacks can now generate positive returns. On average, the attack cost per smart contract was only USD 1.22 (USD 3,476 / 2,849 contracts). This is the hallmark of the hot-weapons era: low cost, high efficiency, and the capacity for large-scale damage. More frightening still, AI hackers continue to evolve.

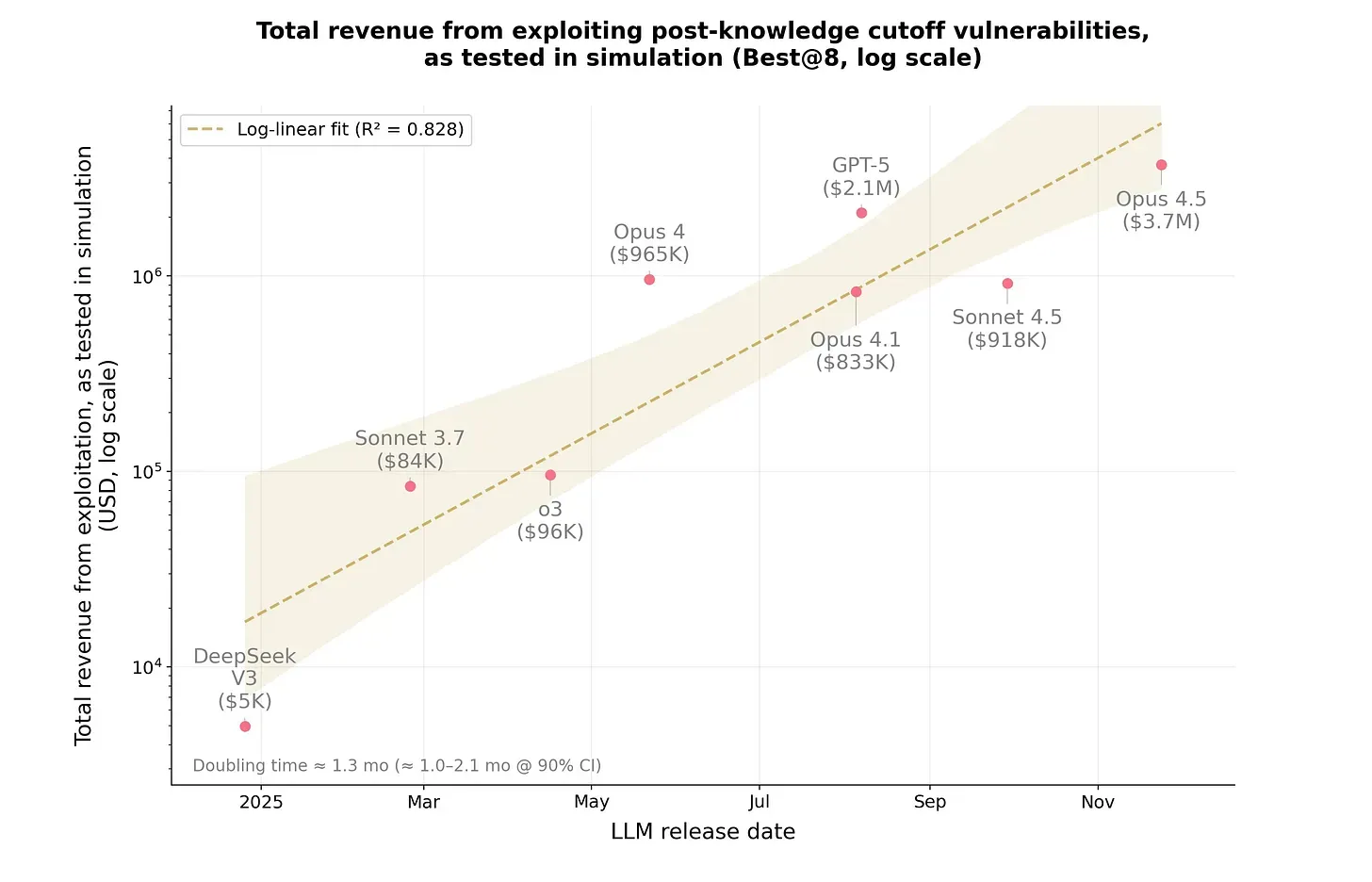

The chart below shows the distribution of attack profits achieved using different language models. The horizontal axis represents the release date of each model, while the vertical axis shows the amount of attack revenue. The newer the model (further to the right), the greater the destructive power (higher up). Early models could cause losses of only a few thousand to tens of thousands of dollars, but with the latest generation—Claude Opus 4.5—AI hacker profits have already surpassed the million-dollar mark.

Of course, some people push back and argue that these figures are merely theoretical results from laboratory experiments. In real-world conditions, attackers would never be allowed to attempt eight consecutive attacks without being detected. On-chain systems are equipped with monitoring and alert mechanisms, MEV bots compete to front-run transactions, and other hackers are also in the field. In practice, launching an attack is far more complex than in a simulated environment.

They are not wrong—but most people are not worried about the present. The real concern is the future. If attacks are launched by AI hackers while developers are still “training their bodies,” we may end up replaying the tragedy of the Boxer Rebellion.

Asymmetric Warfare

Cybersecurity, like national defense, is built on asymmetric power. As long as expected returns exceed attack costs, hackers will be tempted to act. In the past, attack costs were high, so most people lacked the incentive to try. Even so, major hacks occurred again and again. By further lowering the barrier to entry, AI will inevitably make the security situation worse.

Hackers equipped with AI are like someone who has “picked up a gun”: each bullet costs only about USD 1.22 on average, and even failed attacks incur minimal losses. This puts enormous pressure on defenders. What’s more, smart contracts follow the principle of “code is law”—if the code doesn’t explicitly forbid something, then it is allowed.

As a result, defensive thinking must evolve with the times. The focus needs to shift from how to prevent attacks entirely to how to contain damage after a breach.

Security expert Bruce Schneier argues that “humans” must be brought back into security mechanisms. Having humans make the final judgment adds an extra layer of protection and helps limit the scale of damage. In his view, removing humans from smart contracts is akin to crippling oneself.

Another school of thought argues the opposite: humans are the biggest source of risk. They make mistakes, can be bribed, and slow down overall efficiency. Rather than hoping that a hero will step in at the last moment to stop an attack, it is better to encode the rules in advance and let AI participate in defense.

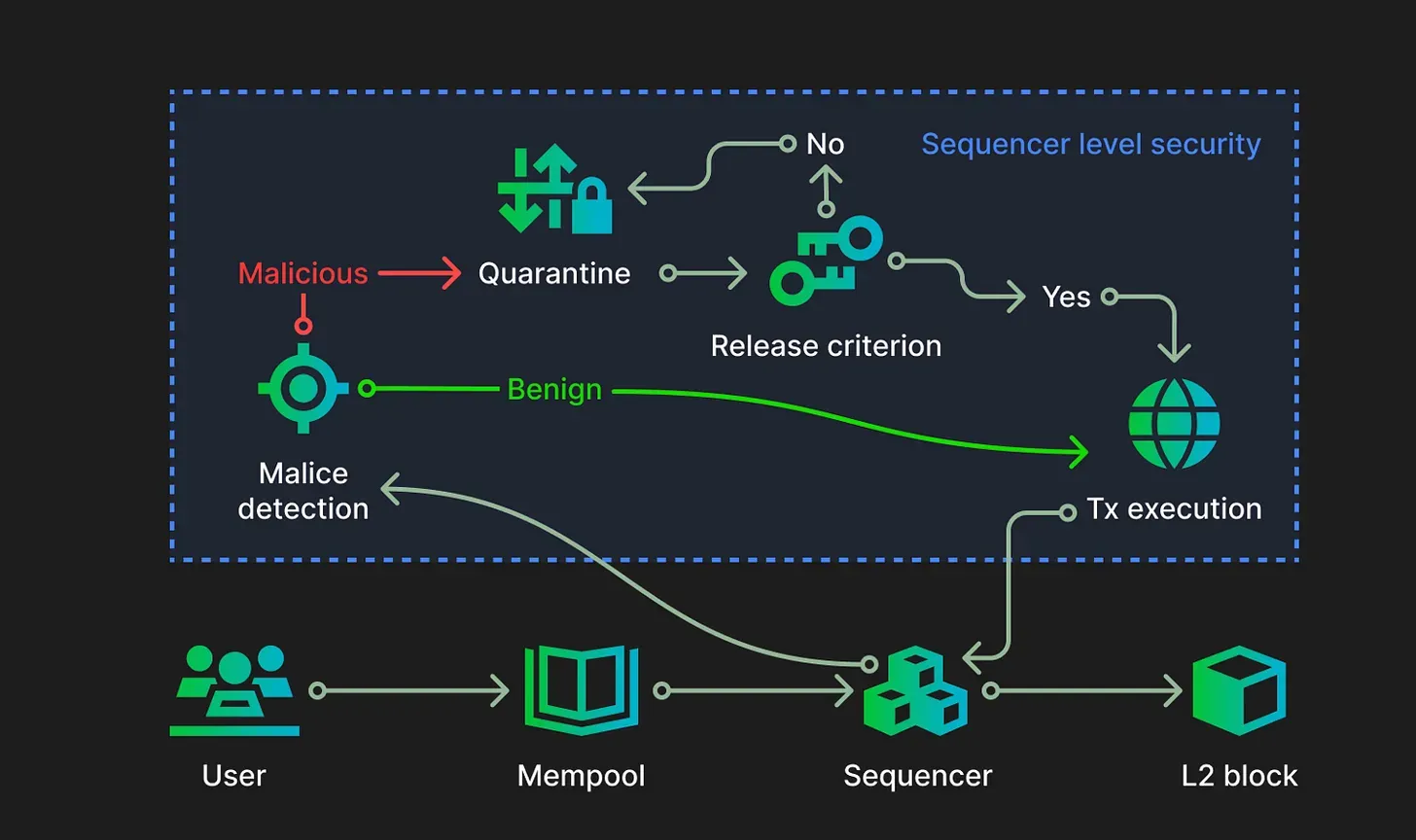

For example, the Sequencer-Level Security proposed by Zircuit 1 introduces a safety 2 valve at the execution layer. It pragmatically assumes that smart contracts will inevitably contain vulnerabilities and that human intervention is rarely timely enough. Before transactions are written to the blockchain, Zircuit adds an isolation mechanism to detect anomalous behavior, thereby constraining attackers. This makes attacks that once seemed profitable far less attractive. As long as attackers decide it’s not worth the effort, the system becomes safer by default.

The “hot weapons era” of smart contracts has arrived. History shows that facing guns and artillery with bare hands is a battle doomed to end in crushing defeat. The future will be an era of AI versus AI. Defensive weapons must evolve accordingly in order to restore a new balance of security.

2 Predictable Airdrops! Zircuit Builds the Blockchain Hackers Hate Most